“Do you speak Tagalog?”

It’s usually the first question anyone asks me when I tell them I am Filipino. This time it was my Uber driver; a man from Punjab probably in his early 60s, who had relocated to Canada 17 years prior. I gave him the same answer I give everyone – which is the truth: I can pick up pieces of conversation when I eavesdrop on conversations and I know a handful of words (hello, thank you, bathroom, coconut, armpit, gross – all the important ones, obviously), but I have never learned how to hold entire conversations and properly express myself using the native language of my Filipino family.

The Uber driver responded with an intense sense of disappointment. To him, it was disrespectful to my Filipino family that I wasn’t familiar with (one of) the traditional languages of the Philippines; it was insensitive of me to be so unfamiliar with such a distinguishable and foundational component of my heritage. His reaction was unexpected to me mostly because I wasn’t expecting him to really care that much; he was just my Uber driver after all and the chances of us ever conversing beyond this car ride was extremely, highly, absolutely unlikely. Before this moment, I can’t remember a time when I was encouraged to feel bad for not speaking Tagalog fluently. People always seemed to accept the fact that English is my first (and only) language. I was born and raised in Canada after all.

But I am biracial. So, maybe I was doing something wrong?

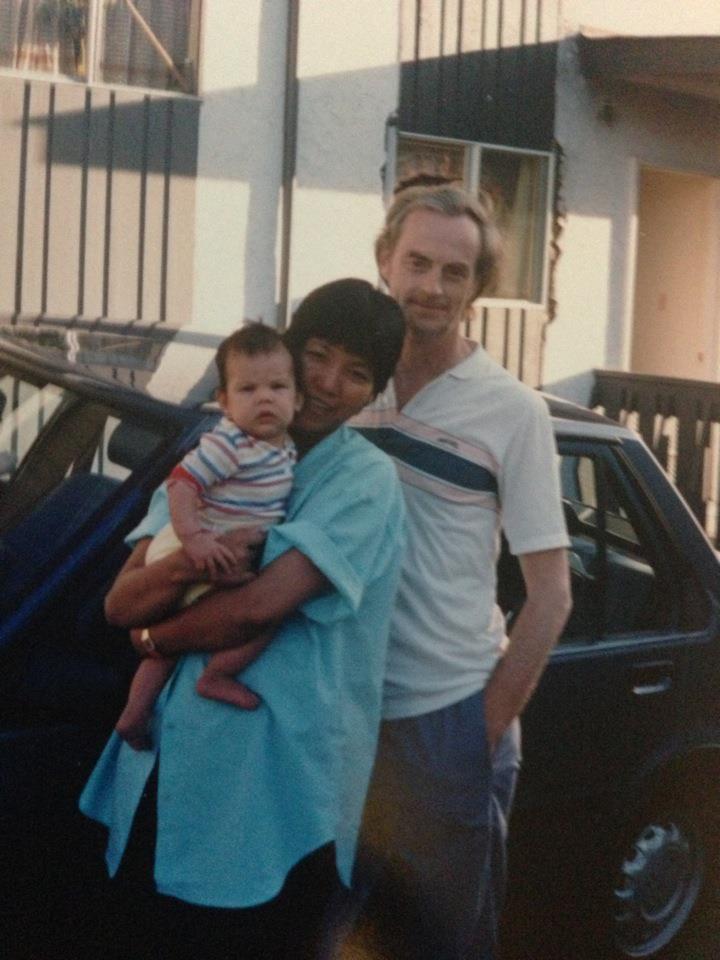

I am Filipino, but I’m also Scottish-Canadian. My mother immigrated to Canada from the Philippines when she was 31 and met my father – a born and raised Canadian with Scottish roots – shortly after she arrived. My mom knew how to speak English upon her arrival since she learned it in school as a child. As she worked towards goals of settling down in Canada, she familiarized herself in new settings and situations where everyone involved spoke English. Her boyfriend, her coworkers, new friends – everyone she knew aside from a few close family members and friends who had also immigrated from the Philippines – used English to communicate and she wanted to wholly submerge and share in those experiences. When I eventually arrived, she wanted me to be able to participate in all the experiences that I would eventually face as well – ones where I would more than likely succeed if I communicated well in English. My mom moved to Canada and married a Canadian, she was determined to get her Canadian citizenship, and she gave birth to a daughter who would also be a Canadian citizen. It only made sense that we, and more specifically I, focus on speaking English primarily.

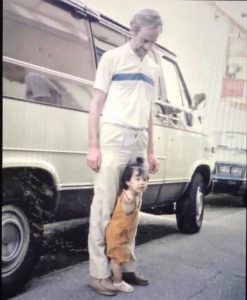

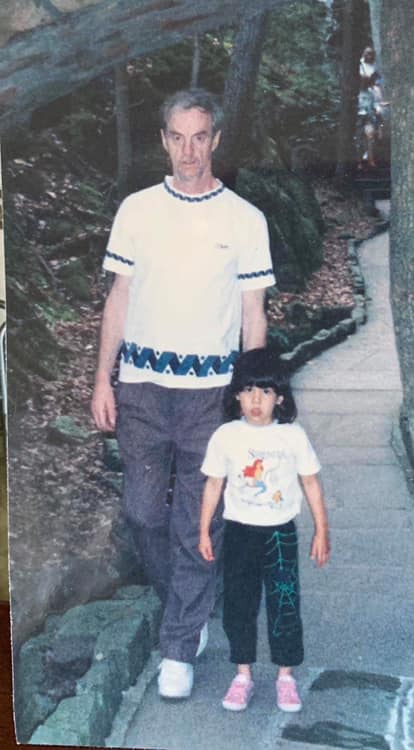

I present as a white person with exotic features. Those aren’t just my words – I’ve based that description off my own personal opinion and a few reviews from others. My mother often points out that she can see my dad when she looks at me; I have his height, face structure, and nose. But she’s quick to remind me that I should be thankful for the genes she passed along that include a caramel skin tone, youthful complexion, beautiful dark eyes and hair. Someone once said I’m a perfect combination of both of them and I agree. Before I really started to grow into my body, I didn’t look that different from all the other kids. I just looked different enough for them to ask questions.

I was on the playground at school with friends around the age of 7 or 8, trying to answer their inquiries about why my skin wasn’t as white as theirs was and why my hair was practically black. “I’m Filipino. My mom is from the Philippines”, I would say as the other kids stared at me with wide eyes. “What is the Phil-pines?” my friends asked back. They had never heard of this foreign place and I had no idea how to explain where it was at the time, except to say: “well, it’s like… China. Like China, but not the exactly same”. Everyone on the playground that day had heard about China before (that’s where everything is made!); they knew China was a real country. But did this Philippines place really exist? Or was I just making it up?

As young as I was, I still felt that overwhelming sense of being an ‘other’. It felt like I was unidentifiable outside my own family, an alien. I even felt different within my own extended family. Up until I was in my teens, I was the only half-Caucasian individual in my mom’s extended family and the only not-full-Caucasian in my dad’s extended family.

Luckily, the tinted colour of my skin seemed to matter less in elementary school once I developed a solid circle of friends and we learned more things about one another beyond the colour of our skin. In fact, it hardly came up unless I specifically referenced my Filipino heritage in show-and-tell or had to include it in a family tree project. When I eventually transitioned into high school though, now being lumped in with various pools of potential new friends from an entire district of other elementary schools, the tone of my skin colour was a noticeable difference and a regular topic of conversation again.

I found myself in a clique of 6 other friends. I was the token Southeast Asian. Everyone in the group knew that the rice cooker in our kitchen was always full of a recently cooked sticky white rice; this was a big selling point for my friends to come over after school. They’d kick off their shoes seconds after walking through the front door and race upstairs to help themselves to bowls of rice topped with butter and soy sauce (deliciously simple!), while poking fun at the fact that it was such a stereotypical appliance for our house to have. My mom often volunteered to leave work early in order to chauffeur my group of friends around town for our volleyball games and tournaments, giving my friends exposure to her English that was highly influenced by a lingering Filipino accent. They used this opportunity to tease my mom for incorrect grammar or unfamiliarity with common slang and her unawareness of western societal connotations. I would occasionally join the ridicule, if only to feel like I was part of something instead of on the other side of it. Luckily, my mom has always had a easy-going attitude and was willing to learn a little bit about being ‘hip and cool’ like her teenage daughter and friends, so she laughed along with us.

The poking fun and laughs was all well and fine, until the word “chink” was brought into the conversation. Within my friends circle, we had earned ourselves nicknames along the way – and somehow that crude slur defaulted as being my moniker. It’s likely that we picked it up in the media somewhere (probably some dumb show like South Park or something – which, I was actually never allowed to watch). Even though it was likely implied somehow that using it wasn’t actually okay, we were dumb teenagers influenced by the toxic information we absorbed and we were completely naïve to the serious implications of throwing that word around or directly using it towards someone. Foolishly, we were probably far more concerned about practically anything else that was actually unimportant – boys, tomorrow’s outfit, whether we were going to get asked to the dance. We really undermined how bad it was to include that word in our vocabulary and to call me – or anyone – that.

Like normal teenagers do, us girls would eventually get in a frivolous argument over some sort of gossip. At least one time that I can remember, in the middle of a heated moment, that slur was used with full intention to hurt my feelings and to imply that I was somehow ‘less than’ because of my Mom’s ethnicity and accent, the colour of my skin, the food we had in our home. Again, it wasn’t okay. Not at all. There were so many other words my friends should have used to channel their aggression instead. But still, they were trying to imply something so poignant.

For some reason, I was wrong. For some reason, I was unacceptable. And the basis of that reason seemed to have something to do with the fact that I was Asian.

My father wasn’t just a white man; he was seemingly translucent, his skin so pale and fragile that it transformed from ivory to pink to fiery red within seconds of being under the sun. By the time I was born, he was already 47 years old with a fairly sufficient life in the book. He’d gotten himself accidentally stranded in Australia once, owned (and sold) a sailboat that he adventured throughout the Gulf Islands in, been married, had two children, gotten divorced, held multiple jobs in various lines of his career in chemical testing and been married again. There were so many times in my life when he talked my ear off with all the details of his lifetime, but I’d be lying to you if I said I paid attention to all of it. I was a little kid and to me – he was an old man. His stories of the ‘olden days’ before technology was invented bored me to death sometimes. Yawn… who cares, I’d often think. BUT, from what I do remember, his life – like most of ours – was okay; a roller coaster of highs and lows. His father died when he was young, his mom worked at Woodwards. They didn’t have a lot of money, but his mom, his sister, and himself managed to get by and live a decent life. And by the time my dad was an adult, he was a kind, well-liked, smart white man. Then, just before I started kindergarten, he was laid off. My mom has gone on the record to say it was because he was too good at his job and his salary was too much for the company to afford.

My dad was in his early 50s when he was laid off and felt discouraged in attempts to look for a new job, so he made the decision to collect an early pension instead. It wasn’t ideal, but it did offer up the opportunity for him to take care of me which saved the family from having to find suitable after-school care. He became a stay-at-home dad, who was able to get me ready for school, walk me to school, pick me up and be available for any unexpected needs in between. He volunteered for almost all the school field trips and events, and eventually spent most of his free time at my school helping kids in the younger grades learn to read and assisting ESL students learning English. My dad didn’t spend his retirement lolly-gagging around. He was taking care of me – a dramatic kid – while also offering his time to stressed out and underpaid teachers. But he wasn’t getting paid himself. And I’m not sure how much his pension was, but with the minimal financial knowledge I do have, I know that there’s no way it was enough to take care of a growing family.

Our family expenses relied solely on the income of my mother, who was an environmental lab technician. All three of us depended mostly on the income of a woman of colour working in a field dominated by men in the early to mid 90s. She was making approximately $24,000 a year. You can go ahead and do the math to calculate that against the cost of living at the time – but I already know that it wasn’t enough for us.

I didn’t get new school supplies at the start of every year; only what was absolutely necessary. I didn’t get a new backpack unless mine was unusable and even then, my father would regularly try to convince me to use his 30 year old (uncool then but totally vintage and cool now) backpack. I could see the stress in my mom’s eyes while she paid for the back-to-school outfits I insisted upon. My lunches weren’t full of the much anticipated Lunchables, fruit snacks, brand name granola bars, or even juice boxes; we couldn’t afford any of it. My dad would pack my homemade soup in an ancient Thermos he had probably saved from decades prior and a peanut butter-butter-banana sandwich wrapped in an empty bread bag (the long, clear type that a regular loaf of bread comes in). We couldn’t fit fancy Thermoses designed with the latest Disney characters or disposable brown paper bags into our limited family budget. I was forced to make do with what we had available.

My parents lived their lives in clothes that had existed in their wardrobe long before I was even a thought in their mind. Every time I wanted some new, overpriced t-shirt, they’d tell me about how they’d owned the shirt they were wearing since before I was born and all the stories that came with the adventures they had while wearing it. (I still have a couple of them in my closet now, because what’s old is cool again). We only ever went on one family vacation, and I think it was before my dad lost his job. I would spend a majority of my life in and with a lot of hand-me-downs from clothes, toys, bikes, video game systems and more.

It was very evident to me that we didn’t have a lot of money. Of course, my mom constantly reminded me of this fact every time I tried to sneak something into her shopping cart at the grocery store or when I begged her to buy me something new from the mall. But I also saw it every time I went to friends’ houses, where they had two parents who were both white and employed.

Our family lived a life very different from theirs and I knew a big part of it was because only one of my parents had a job, while the other one stayed home or volunteered. In our family dynamic, my white father stayed home while my Filipino mother went to work everyday. She would come home and complain about being overworked, about being looked over by management or being undermined by those above her. When I met her coworkers at holiday events or summer barbecues, most of them were white men and women, and it was noticeable that all the people of colour formed their own sub-group and stuck together. Whenever I was upset at my mother for not buying me whatever fancy, expensive thing I demanded, my grandma (her mother) would often sit me down and gently explain to me that my mother worked so hard to give me all that I already had; she would tell me that my mom was was doing her best despite the circumstances and I that I should be more understanding and grateful. Without having it explicitly said at any point, it seemed as though my mom didn’t have the same opportunity or advantages as many white people we crossed paths with. That the income she made to provide our family just wasn’t as much as the other families had, but it was definitely better than what we’d have if we were in the Philippines.

I didn’t have all the details and I was still too young to completely understand, but I had a hunch that the different shade of her skin and my own were reasons we didn’t seem as fortunate as other people we knew.

I was too young to remember my first trip to the Philippines, but I went back a second time during Spring Break of grade 11. My family welcomed me with open arms after not seeing me for a decade (or more), but they – and many strangers – also adored and admired me, continuously commenting on my ‘idyllic’ skin tone, features, and beauty. They favoured my lighter skin tone and the prominent features I had inherited from my father. They repeatedly told me how lucky I was and I was often told I was the ideal candidate for a modelling career in their country.

In the Philippines, fairer skin is a sign of upper class and wealth. People with the privilege of working in an office, using their own vehicle for regular transportation across the city, the luxury of affording whitening lotions and skin creams tend to have fairer skin because their lifestyle doesn’t require them to be in the sun all day. Those who live in poverty – as much of the Philippines’ population does – are stuck spending their days underneath the powerful sunbeams. They walk, work, live, without shade or protection from endless UV rays and their skin shows so. The deep, rich, dark tone of their skin is their brand that represents their lower status, lack of income, inability to find shelter from the sun.

Many people who live in the Philippines idolise the life associated with having white skin. They want to be white too, if only to experience the wealth and freedom that porcelain skin colour affords instead of the struggle they face in their country stricken with poverty and ruled by dictatorship. They see whiteness as a symbol of power and opportunity, a better life.

My blended skin tone was a picture perfect vision for so many Filipinos in my immediate family. Sure, I represented who they were, but I also represented what they so desperately longed for.

My mother grew up in Manila with 7 brothers and sisters. Her father was an administrator for the Red Cross while her mother stayed at home to take care of the family, occasionally offering sewing and catering services for locals to help with finances. Money was tight. I’ve been told stories about how all the siblings shared one mattress for sleeping, how their house flooded because of typhoons, how my aunt and uncle scavenged for extra pesos by selling random trinkets. All 8 children went to college at the insistence of my grandparents, but in order for them to all afford finishing with their degrees, they all contributed to one another’s tuition. Once one sibling graduated with their degree and found a job, they would help out with helping to pay for the next sibling to graduate, and so on. Eventually, they all graduated and strived to live up to the expectations my grandparents had suggested. They all wanted to build a better future for themselves and their eventual familie; to excel and fare much better than the life they had lived so far.

And that’s why my mom moved to Canada.

She finished her chemistry degree and ventured across the Pacific Ocean to greener pastures. Canada was going to offer her opportunities and a life that just weren’t possible in the developing country she had spent her whole life in. She came here to achieve more, to live a life different than anything she had known so far.

She had big plans: she was going to get married, start a family, and flourish. And when she did have a child, she wanted to make sure that child didn’t have the same life she had growing up.

English is a component of the Filipino curriculum. It’s also regularly integrated into conversation alongside Tagalog; they frequently incorporate English words among convoluted Tagalog sentences. My Lola (my Filipino grandmother) was also an avid reader, learning English through the books she so often read, and passed that along to her children. So when my mom arrived in Canada in 1982, she was well versed in English but also still spoke Tagalog regularly.

When she crossed paths with my father, he was a 40-ish year old man who had no ambition to learn a new language. Fair enough. Eventually, they brought me into the world and I was undoubtedly going to grow up surrounded by English speaking peers, friends, and teachers. It really only made sense for us to speak English at home and in our everyday lives. There was one small moment when my parents considered enrolling me into a French-immersion elementary school (because, Canada), but quickly decided that neither of them had the energy to learn fluent French with me.

At family gatherings, my mom would revert to speaking Tagalog while she interacted with family friends and her siblings. In these scenarios, when I was desperately trying to grow up faster by sitting at the adult table, I would learn a handful of words through exposure and curiosity. But most of the time, no one was concerned that I didn’t have the ability to converse fluidly with Tagalog.

I was a Canadian. My mom was now a Canadian. It was important to her that both of us live in a way that aligned with the life she had moved here to live. Speaking English was a necessity to get by where we lived, so that’s what we spoke.

After being called a ‘chink’ in high school, I can’t remember a time when the subject of my race felt like a significant issue; no one seems to address the colour of my skin these days with much concern, so I don’t really think about it unless they want an explanation.

If I’m being honest, I see myself as a passable caucasian more than a Filipino. When I look at myself in the mirror, I see my dad’s nose, facial structure, and his height. I do have my mom’s cheekbones and smile, but my skin is nowhere near being as dark as hers or her other family members. My hair isn’t as dark either, my nose is different, my eyes are different. I look different from my Filipino family in so many ways and it’s difficult for me to associate myself with them. Even when I meet Filipinos out in public – grocery store clerks, nurses, neighbours – they all react with astonishment when I tell them I’m Filipino, too. In so many of my experiences with other Filipinos, I don’t feel the same as them; I don’t feel like one of them. I’m this anomaly, this unexpected but pleasant surprise. I am an other.

But I am Filipino.

But also, I’m Scottish.

I’ve told that story about my Punjabi Uber driver seeming frustrated and saddened by my inability to converse in Tagalog because it’s one that really hit home for me. When I exited the vehicle, I was left wondering if in fact I’d let down an entire half of my existence and the family behind it. I started questioning who I was and whether or not I might actually be a disappointment to my Filipino family.

Had I picked one side over the other? Was I also guilty of treating Filipinos like a minority, the same way so much of society still does? Am I a horrible person?

More than ever before I felt, and continue to feel, challenged by my existence.

I am a woman of colour, who grew up feeling out of place and unfortunate. I was called out for the colour of my skin and the weird food my extended family ate and the obviously counterfeit Nike apparel my grandparents would gift me from their trips to the Philippines. I was designated as Asian representation within my friend groups and called racial slurs. No, it’s not to the same extent and severity as so many other persons of colour, but I have experienced the racial stigma.

Simultaneously, I’ve managed to blend in with the crowd and fortunately bypass a lot of the misfortune associated with minority race. My skin isn’t translucent like my father’s, but I have been perceived as someone who has possibly just spent a little too much time in the sun. I’ve been told that it’s usually just a passing thought in people’s minds that I look like someone whose heritage lies in the poorest parts of a developing country.

I know that the Uber driver wanted to make sure I was proud of being Filipino and that I fully embrace that part of who I am. I do. I don’t speak Tagalog, but I want to speak up about who I am and what it means to be someone who’s experienced the racial inequalities.

I want to share my story, especially about who my mother is and why she raised me as she did; why we live here and why it wasn’t a priority to teach me Tagalog. I want people to know that I do appreciate and respect my Filipino background in so many ways because it is something my family continues to speak proudly about. But those same family members and others also taught me to appreciate the advantages I have of being born and raised in Canada.

Tagalog is used frequently in my family for many reasons – to emphasise important context, to properly explain serious situations, to keep secrets. In situations that allow me to, I try to incorporate myself into Tagalog conversations and identify key words or phrases to at least understand what’s going on. I ask questions and learn new words when I can. Where I lack linguistic abilities, I make an effort to recognize the influence of my heritage and the lives before me that were lived in a way that was so much more difficult than anything I could imagine. I appreciate the sacrifices my mother made to give me the life I have now. I’ve listened to endless stories from her, my grandparents, my aunts and uncles, and cousins who often share how different life was for them back in the Philippines and how much life has changed since they arrived in Canada.

My mom moved to Canada to give herself the opportunity to thrive. Through broken English, she advocated for herself in a male-dominated industry and work environments, and worked hard to provide for her family despite uncontrollable odds that worked against her. And that’s exactly why it was never pushed on me to fluently express myself in Filipino. She wanted me to express myself in a way that those around me would recognize and understand, that would be appreciated by the masses. She didn’t want me to face the racial stigma she did as I moved through the world. She wanted me to fit in, to feel like I belonged. She wanted me to feel like the white person so many Filipinos want to feel like.

In so many other ways – through favourite meals and family recipes, via regular vacations to different islands in the Philippines, by encouraging me to maintain strong relationships with my Filipino family and constantly sharing stories of life ‘back home’ – my mom instilled my passion for the Filipino culture that makes up a portion of my existence. I don’t have Tagalog, but have favourite family recipes and memories associated with my Filipino side. And you can see Filipino in my physical features; those who pay attention to finite details can see it.

I also want people to know that I recognize my advantage of being born here and more importantly, the privileges that my father’s genetics afford me in comparison to the lives lived by family members who were born in a developing country and immigrated here later. I know that many consider me lucky to have a father with Scottish roots.

I have a unique experience, where I’ve seen both sides of the story. I am a mixture of cultures with a blended experience because of my mom’s ethnicity and the colour of my dad’s skin. It’s a combination that has taught me a lot over many years about the realities of minority race and the privileges of whiter skin. I’ve faced the hardships of growing up with a mom with an accent and brown skin and of looking different than my friends. I have also lived with advantages that certain family members dream of – lighter skin, the presentation of familiarity, the ability to blend in.

I don’t speak Tagalog, but that doesn’t mean I don’t embrace or recognize what it means to be Filipino. I’ve lived it.

I know what it means to be a person of colour because I am one.

I also happen to be Caucasian, with Scottish ancestors. Because I speak English, that’s the language I use to tell a story about knowing there’s parts of me that are different from all the white people around me.

I was not raised to be one or the other. One isn’t better than the other.

I have grown up as – and I am now – both at once.

Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

This was heartfelt and beautifully written.

Well said Jennifer and I am proud to be your Filipino Aunt. I”ll treasure you, not for being a Filipino or a white Canadian but for being a kind and loving person you are. I love you.

Tita Elsie